The worker bee. The infertile female of the hive. The honey makers. Let’s see what are the body parts of a bee and what makes a worker bee different than its relatives.

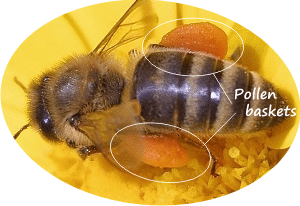

The smallest members of the hive, the worker bees represent the majority of bees from the colony. They are all female but have undeveloped ovaries, thus incapable of reproduction. Compared to males and queen, worker bees have specialized body structures, such as brood food glands, scent glands, wax glands and pollen baskets, which allow them to perform all the necessary hive tasks.

How does a worker bee look like?

A bee’s body is covered in lots of fuzzy, branched hair, which collects pollen and helps regulate body temperature.

Instead of internal skeletons, insects have exoskeletons, which are tough outer coverings made up of several layers. The bees’ body has an exoskeleton made of small, movable plates of chitin, a horny, waterproof substance.

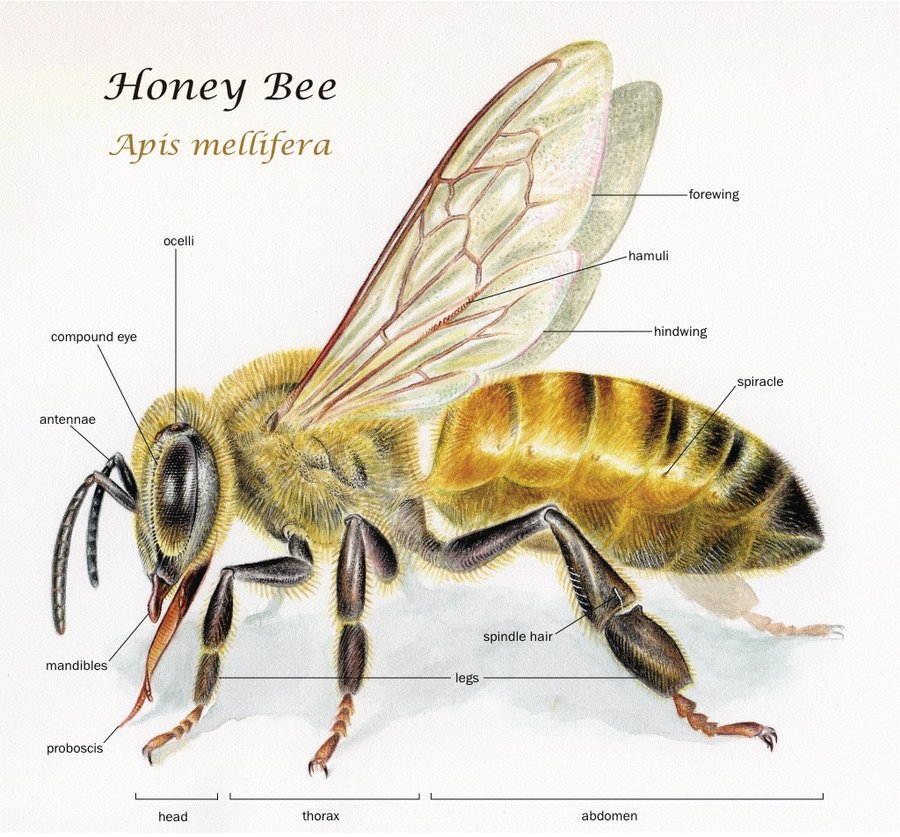

The body has three parts: head, thorax and abdomen.

The head

It as a triangular shape and contains:

The brain:

It has about 950,000 neurons. Honey bees have excellent memory processing and learning abilities, necessary for long foraging flights away from their hives. The brain coordinates and regulates the functions of all the bodily systems. While only about 1 cubic millimeter in size, the honey bee’s brain contains some of the most densely-packed neurophil tissue known in any animal brain.

The antennae:

A bee has two sensory antennae, which are covered with thousands of sensory cells for touch and smell. A bee’s sense of smell is much more acute than any mammal’s and is very important for locating food and in communication between hive members. These sensitive organs also relay information about air speed and orientation during flight.

The eyes:

A honey bee has five eyes: three simple eyes, aka ocelli, and two compound eyes.

The simple eyes, the ocelli, aren’t used for vision, but to detect changes in the intensity of light.

The compound eyes are made of lots of small, repeating eye parts called ommatidia. Each of a honey bee’s compound eyes contain over 6900 separate facets, allowing it to see in front, to the side, above and below itself.

Those two large compound eyes are well suited for detecting movement. In fact, honeybees can perceive movements that are separated by 1/300th of a second. Humans can only sense movements separated by 1/50th of a second. Were a bee to enter a cinema, it would be able to differentiate each individual movie frame being projected.

In addition, bees can perceive all the colors visible to humans except for red, which appears black to them. Honey bees, like many other insects, can see UV light as a separate color, which we cannot. Bees can also detect the polarization of UV light, which aids their navigation on cloudy days, when the sun is not visible. Read more about bee’s senses.

picture source Matt Inman via commons.wikimedia

The mouth:

It has complex mouth parts that used to eat and drink. The sizes and shapes of these parts can vary from species to species, but generally bees have:

– Paired mandibles, or jaws. Mandibles which are strong and very useful. The jaws are attached to powerful muscles, and can be used to pick up and remove debris from the hive, to attack intruders, and to delicately manipulate the wax into perfectly formed honeycombs.

– A labrum and two maxillae which are like lips.

– A proboscis, supported by maxillae and labrum, which is a tube for collecting nectar. This “tongue” is well adjusted for lapping up nectar from deep inside of flowers, its average length is 6.4 mm.

Hypopharyngeal gland

Possessed only by worker bees, this hypopharyngeal gland produces royal jelly, or bee milk. This rich blend of proteins and vitamins is fed to all bee larvae for the first three days of their lives, after which workers and drones are fed a mixture of pollen and honey. When a female larva is fed continuously on royal jelly, she will rapidly develop into a queen bee. This nutritious diet will remain the only food that a queen will ever consume, allowing her to maintain a high level of continuous egg production.

The pharynx is the first section of the alimentary canal. Strong muscles here provide suction to draw in nectar from flowers. This is also the site for taste reception in insects.

Salivary glands are located in the front of the thorax, and are connected to the mouth by a duct. This gland produces enzymes which aid in the breakdown of food. Especially the enzyme invertase, which breaks down the sugars in nectar, and is essential to the process of converting it into honey.

The thyorax

The thorax is primarily used in locomotion, as the attachment site for six legs and four wings. The ventral nerve cord, heart and esophagus pass through, but most of the space inside the thorax is taken up by sets of powerful flight muscles. An aorta in the thorax pumps blood, or hemolymph, directly over the organs rather than through a system of vessels. Oxygen floats in the hemolymph without the use of red blood cells, so the fluid is colorless instead of red.

Salivary glands are located ventrally, near the front of the thorax, connecting by a duct to the oral cavity in the head.

The wings

A bee has two pairs of wings and three pairs of  legs connect to its thorax. The wings are extremely thin pieces of the bee’s skeleton. In many species, the front wings are larger than the back wings. A row of hooks called hamuli connect the front and rear wings so they beat together when the bee is flying.

legs connect to its thorax. The wings are extremely thin pieces of the bee’s skeleton. In many species, the front wings are larger than the back wings. A row of hooks called hamuli connect the front and rear wings so they beat together when the bee is flying.

They can forage up to three miles from their hives, and reach speeds of 15 miles per hour. When at rest, the bee can unhook its wings and fold them back. (Photo by Jon Sullivan, pdphoto.org)

A honey bee distinctive buzz is given by the frequency of the movements of the wings. Bee’s wings stroke 11,400 times per minute!

The legs

A bee’s legs as just as any other insect’s. It has 3 pairs of legs. Starting from the body, a leg has the following parts: coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia and tarsus. They all act like the bee’s hip, thigh, shin and foot, and tiny joints separate each segment. A bee’s legs can also have several specialized structures, including:

– Brush, comb and basket-like hairs for collecting pollen;

– A pad and claw for holding and manipulating objects;

– A small groove for removing pollen from the antenna;

– A press for packing pollen

The pollen basket, or corbicula, that we see on their legs, is made of long stiff hairs that curve around a wide flattened section of the worker bee’s back leg. Stiff hairs on the other legs are used to comb pollen grains from the bee’s body, which is compacted and stored in the pollen basket for transport back to the hive.

The abdomen

It is equal in length to the wings.

It protects the organs of the digestive system. Here there are the heart, venom sac, and several glands. The reproductive organs are also located in the abdomen. In a laying queen bee, the ovaries take up much of the space here, and account for the larger size of the abdomen.

It has almost no appendages, but it houses nearly all of the bee’s internal organs. Like all the other insects that breathe air, bees don’t have lungs. Instead, a system of branching air tubes, or tracheae, carry oxygen into the bee’s body and reaches all its. These passageways are called spiracules,and they allow the bee to breathe.

The honey crop

The abdomen also holds a tube-like digestive system that includes a crop, or honey stomach, is where the bee stores collected nectar for the trip back to the hive without digesting it. A muscular valve called the proventriculus can be closed, keeping the nectar from passing into the stomach. The crop is expandable, allowing the bee to carry a larger load. Back in the hive, the contents of the crop can be ejected back through the mouth for storage in a honey cell or to feed other bees by trophallaxis.

The true stomach

Aka ventriculus, it is the site of primary digestion for pollen and nectar. Coiled around in the abdomen, it is actually about twice the length of the bee’s body. The epithelial cells that line the stomach wall are the site of attack by the microsporidia Nosema.

The hind gut

It is composed of the intestine and rectum, where reusable metabolic products are reclaimed and excess water is reabsorbed into the body. The rectum is also distensible, and can hold a large volume of waste matter.

A lot of people was asking where do bees poop. Especially in winter. Well, bees keep their hives very clean, and will hold their wastes until they can make a “cleansing flight” outside of the hive. In climates with long, cold winters, bees can actually wait for weeks or months to perform this task.

The Malpighian tubules are numerous and connect to the basal end of the hid gut and float freely in the abdominal cavity. They function much like the kidneys of vertebrates, removing excess salts and metabolic wastes from the blood and concentrating it into the intestine, where it can be removed.

The Wax Glands are on the underside of the bee’s abdomen, and they secrete flakes of beeswax, which are used to build the honeycombs. Many bees work together to produce and form the wax that becomes their home. Bees must consume at least eight pounds of honey in order to metabolize one pound of wax.

The stinger

Female honey bees have stingers. Apis Mellifera. But there are some bees that don’t have stingers.

When their life is in danger, or they interpret the smell, noise or colors as a threat to their hive, they sting. This stinger has barbs, just like a phishg hook, and when they are trying to pull it out, part of the bee’s abdomen is torn apart. The bee dies soon after that.

This usually happens with the human skin, but bees with barbed stingers can often sting other insects without harming themselves. Queen honeybees and bees of many other species, as bumblebees and many solitary bees, have smooth stingers and can sting mammals repeatedly.

The venom sac

It’s connected to the stinger and holds a mixture of protein chemicals (the venom) and alarm chemicals. These proteins can quickly cause a painful localized reaction in vertebrates, which can be severe to life-threatening in highly sensitive individuals.

When a bee stings, the barbed shaft of the stinger is left behind, along with the venom sac. An attached muscle continues to pump venom through the stinger, even after it has been disconnected from the bee. For this reason, a bee stinger should be removed immediately by scraping it with a credit card or pocket knife blade, and not by pinching it, which can forcibly inject the venom into the skin. See what to do immediately after a bee stung you.

Why yellow and brown bands on their bodies?

Males’ stripes are more visible.

The biologic explanation would be that the males come from unfertilized eggs and so their physical characteristics rely only on those of the queen. Since the powerful color of their stripes. Other insects hide when predators are close by, but the brightly colored bodies of the bees act as a warning to predators or honey robbers. “Stay away! Our sisters, the females, with dangerous stings, are here.”

But their flights away from the hive are so rare, that we remain at the scientific explanation, with the carrying of only the queen’s genes.

Females’ stripes are less visible.

The queen mates several times before laying eggs, so the working bees from one laying could have been produced with the sperm of different males, thus resulting a varied coloration. Anyway their color isn’t that important in fighting the enemy, as they do possess stings and can protect the hive and the colony.

These colors and the intensity of them also varies between species. Some bees have their body predominantly black, while others have dark to light stripes.

As for why did the universe choose to paint them in exactly these colors, our scientists haven’t found an answer yet.

Picture sources:

bee’s head picture credit David Davies via flickr.com;

bee’s hive picture source pdphoto.org;

bees’ pollen baskets source pdphoto.org;

Anatomy of a bee picture credit Noel Badges via tumbrl.com

References:

uaex.edu;

animals.howstuffworks.com;

wikipedia.org;

pbs.org