It’s a jungle out here. We fight each other, we eat each other. The small animals have their weapons against bigger animals. However, some of them have developed anti-predator behaviors that can be considered an evolutionary consequence of adaptation to the threat of natural enemies.

The enemy is here the Japanese Giant Hornet. It doesn’t feed on fruit, but on smaller insects. Regular honey bees, Apis Mellifera, use their stingers to counterattack a hornet, as they do with any other enemy. But it doesn’t work with this hornet. So, the regular honey bees get killed.

However, the Japanese honey bees, Apis cerana japonica, use a different strategy, called “hot defensive bee ball”. It’s a samurai bee style, of course, we are talking about Japanese here! 🙂

What is the Japanese giant hornet?

On its scientific name, Vespa mandarinia japonica, the Japanese giant hornet is a subspecies of the worlds largest hornet, the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). It can reach 5 centimeters long, and has a wingspan greater than 6 centimeters. It has a large yellow head with large eyes, and a dark brown thorax with an abdomen banded in brown and yellow. The Japanese giant hornet has three small, simple eyes on the top of the head between the two large compound eyes. I’m sure the SF film writers got a lot of inspiration from these creatures! You have to admit they are creepy!

A single hornet can kill 40 regular honeybees in a minute; a group of 30 hornets can destroy a hive containing 30,000 bees in a little more than three hours. The hornets eat the honey, kill and dismember the bees leaving the members behind. They take only the bees’ thoraxes (as it is the most nutrient-rich body part), and the bee larvae to feed their hornet larvae with them. Just like human barbarians!

30 to 40 people die every year in Japan, stung by the giant hornet. In 2013, the Asian giant hornet killed 41 people and injured more than 1,600 people in Shaanxi province, China. Yet, in many Japanese mountain villages the hornet is fried and eaten, even considered a delicacy. (their turn to be eaten!)

Have you ever heard of VAAM?

It comes from vespa amino acid mixture. It is the fluid that results in the process of chowing the prey (the honeybees) so it can become a paste good to feed to the hornets’ larvae. The hornet workers eat the fluid and this will enable intensive muscle activities over extended periods, allowing them to fly 100 kilometers (62 mi) per day and reach up to 40 kilometers per hour (25 mph).

So, why am I asking if you heard of VAAM? Because humans have learned a lot from the animal’s world. Studying the hornets, we are now artificially producing synthetic VAAM, which is very efficient as a dietary supplement, to increase athletic performance.

Hot defensive bee ball

Because the sting doesn’t help, Apis cerana japonica, the J

apanes honey bees, confront this incredible giant hornet, using a different fight strategy called “hot defensive bee ball formation”.

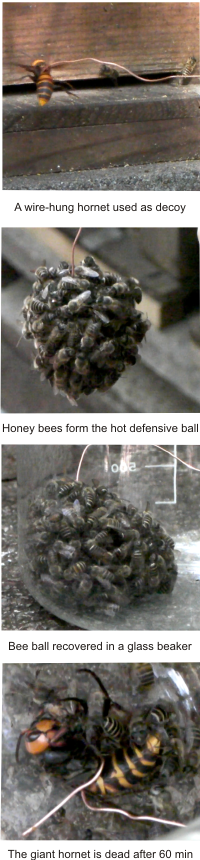

The Japanese bees are usually attacked in autumn. The hornets try to steal their larvae and eat their honey. But if the hornet scout is inside the hive, 500 worker bees will form a spherical assemblage around the hornet, trapping it inside like in a ball. The honeybees vibrate their flight muscles and produce heat. The temperature in the ball quickly rises to almost 46°-47°C, which is lethal to the hornet but not to the honey bees. (The bees resist up to 50° C). In addition, the exertions of the honey bees raise the level of CO2 in the ball. The temperature is maintained for almost 20 min. The combination of high temperature and high level of CO2 is lethal to the hornet. It will be killed in 30 to 60 minutes, after the bees have started to form the ball.

Killing the scout will prevent it from summoning reinforcements that would erase the entire colony.

This strategy however, belongs only to the Japanese honey bees. The European species Apis Mellifera, know only to sting. Which is ineffective, considering the rigid exoskelton of the giant hornet. This is why they are incapable of defending themselves and get killed.

Why only the Japanese Honey Bees can form the hot ball?

A Japanese research team from The University of Tokyo studied what was happening in the bees’ brains while forming the ball. They extracted the insects from a hot defensive bee ball and analyzed their brains. What they found was that there was a marker gene present, which was not found in the other honey bees.

To simulate an invasion, the researchers introduced a hornet on a wire to a hive. Worker bees quickly gathered around it, formed a ball, and started vigorously to vibrate their flight muscles to generate heat. An hour later, the hornet was cooked alive.

The team measured increased activity in the structure of the brain responsible for learning and memory in insects, called mushroom bodies. Interestingly, the same area was activated when the bees were exposed to 46 °C heat in the lab, suggesting that the activity is triggered by temperature when the bees form a ball.

According to the researchers, the bees must maintain a very precise temperature in the ball. “If the temperature drops below 46 °C, the hornet will not be killed, whereas if it’s any hotter both the hornet and the bees will be killed,” he says. The team thinks that the neural activity causes bees to modulate the movement of their flight muscles to maintain a constant level of heat.

Giant hornets are predators native to Asia that resist being stung, suggesting that the behavior of the Japanese bees evolved as an adaptation to tougher enemy.

The power of 500!

Related articles:

• Can a honey bee see, smell, taste, touch, speak?

• Do honey bees communicate?

• The jobs of a bee. What is the life of a bee?

• How to treat bee sting

• The honey bee QUEEN

Picture source:

Giant Japanese Hornets: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Vespa_mandarinia?uselang=en-gb;

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Insects1Robinson1871.jpg?uselang=en-gb;

Info source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/;

http://www.plosone.org/;

http://www.newscientist.com/